I am going to officially pause this blog for an indefinite period.

I have done a couple of posts since this past May, when my wife died.

I've tried to stay connected to some essential part of me that enables me to read and write, to critique, but I think the writing I need to do right now is not for public consumption.

I don't know how else to say it, because it seems as simple as that.

I'll be back here, I believe. Eventually.

Friday, October 26, 2012

Friday, October 12, 2012

Mo Yan

Congratulations to Mo Yan for winning the Nobel for literature, 2012.

I saw this writer once at the Toronto Reference Library and mentioned him in a 2009 blog post here about Richard Van Camp, connecting Mo, Richard and William Faulkner.

I saw Richard talk about his writing once, at a First Nations cultural festival at Harbourfront in Toronto, and he spoke about the stress of modernity on Aboriginal communities in the north. His stories attempted to capture that. I told him afterwards that I had seen Mo Yan say something similar about his work. It was about capturing the stress of modernity on rural communities in China. Yan had said he had learned to write about that partly from William Faulkner.

Strange connections? Not at all.

When I saw Yan, he didn't read. He didn't speak English. He was interviewed by translator. He spoke about how the Communist government allowed him to publish his novels while also requiring him to write detective drama for television. His novels sold in the multi-millions, but mostly in pirated copies. He shrugged.

So it goes, as Vonnegut would have said. Did say.

It's a moment I will never forget. Here was a guy writing with a market audience, but without a market payoff. Writing detective dramas for TV, not because his novels didn't sell, but because he was given no alternative. His novels sold, but he didn't reap the profit.

What's to say, except good job Nobel Committee, but don't jinx the guy.

Hemingway kept a couple of novels in draft in a vault in Havana, I once read. Because he didn't want to sell them because they could be sold. He wanted to be sure that they were good. Wanted them to rest and test the tides of time.

Compare and contrast with J.K. Rowling.

I have the above newspaper headline clipped to the wall above my desk.

Every time I read that I shudder.

How much larger could you get?

So, Mo, resist the urge to go for the gold. Resist the urge to be all Nobelesque.

Stay in the groove, man. Just, go.

I saw this writer once at the Toronto Reference Library and mentioned him in a 2009 blog post here about Richard Van Camp, connecting Mo, Richard and William Faulkner.

I saw Richard talk about his writing once, at a First Nations cultural festival at Harbourfront in Toronto, and he spoke about the stress of modernity on Aboriginal communities in the north. His stories attempted to capture that. I told him afterwards that I had seen Mo Yan say something similar about his work. It was about capturing the stress of modernity on rural communities in China. Yan had said he had learned to write about that partly from William Faulkner.

Strange connections? Not at all.

When I saw Yan, he didn't read. He didn't speak English. He was interviewed by translator. He spoke about how the Communist government allowed him to publish his novels while also requiring him to write detective drama for television. His novels sold in the multi-millions, but mostly in pirated copies. He shrugged.

So it goes, as Vonnegut would have said. Did say.

It's a moment I will never forget. Here was a guy writing with a market audience, but without a market payoff. Writing detective dramas for TV, not because his novels didn't sell, but because he was given no alternative. His novels sold, but he didn't reap the profit.

What's to say, except good job Nobel Committee, but don't jinx the guy.

Hemingway kept a couple of novels in draft in a vault in Havana, I once read. Because he didn't want to sell them because they could be sold. He wanted to be sure that they were good. Wanted them to rest and test the tides of time.

Compare and contrast with J.K. Rowling.

I have the above newspaper headline clipped to the wall above my desk.

Every time I read that I shudder.

How much larger could you get?

So, Mo, resist the urge to go for the gold. Resist the urge to be all Nobelesque.

Stay in the groove, man. Just, go.

Monday, September 3, 2012

A summer of reading

I started the summer of 2012 by reading Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway and Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot.

These were the first two books I read following my wife's death from breast cancer in May.

I wrote an essay about "returning to reading," and it was published by the literary blog Numero Cinq in July.

Other books I read over the summer:

- Off Book by Mark Sampson

- Hamlet by Shakespeare

- Fathers and Sons by Turgenev

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

- Flaubert in Egypt by Gustave Flaubert

- The Victim by Saul Bellow

- Widower's House: A Study in Bereavement (or how Margot and Mella forced me to flee my home) by John Bayley

I'm also poking my way through:

- A Tramp Abroad by Mark Twain

- Essays and Aphorisms by Arthur Schopenhaur

- Sentimental Education by Gustave Flaubert

- This Side Jordan by Margaret Laurence

- Saints of Big Harbour by Lynn Coady

- Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

- Long, Last, Happy by Barry Hannah

Do you see a pattern? I don't see a pattern.

Some of these books are works I've "meant to get to" and now find myself seeking out. Some I've picked up in used book shops. Others have been on a shelf in my house, ignored.

There's a lot of ribald reveling in the oddity of humanity in the above, but there's also some earthy earnestness.

I found in Turgenev cynicism that was starkly contemporary, and in Huck Finn's Mississippi adventure a freakishness consistent with the current U.S. election cycle.

I felt Hamlet's pain as my own, and, like Sampson's protagonist, remembered how wild and liberating the internet seemed in the 1990s.

Bellow's early novel contains both his trademark singing souls and bureaucratic absurdity of a Beckettean order.

But Flaubert in Egypt? Twain in Germany? Alien and eccentric. The diversity of human weirdness is duly noted.

Schopenhaur? I read the first paragraph and laughed. Likely not what he intended, but there is a dark humour there that I've seen before and like. I went to Schopenhaur after reading The Pugilist at Rest by Thom Jones. Schopenhaur is referenced throughout that book, and I was curious for more. The introduction compares Schopenhaur to "our own great pessimist" (Shakespeare), and I hadn't thought of the Bard that way before. I'd thought of him as a poet of chaos (like Bob Dylan). But pessimist? Hmm.

A Sentimental Education I'm drawn to, I think, because it's other worldly. Most of my life I've felt more akin with 20th century literature and not much desire about the 19th century so-called masters. But this summer that has changed. The contemporary has become fraught and I want to read the back catalog.

Early Margaret Laurence, set in Africa. Curious. Barry Hannah, the selected. Wild and wonderful. Lynn Coady just because I haven't got around to that one yet.

I started my essay on Woolf and Beckett without a voice, or with the most meager of voices, and with the faintest of ears. I was only getting one frequency, and I couldn't make out the full signal.

I can hear more now. I can speak more now. But the world is different. There has been a break from the past that will never heal. Beauty, however, remains, and much else. A deeper recognition of the mixed-up-ness of everything. A recognition that there is no resolution, no end to the storytelling.

The mighty river of literature just rolls on and on.

These were the first two books I read following my wife's death from breast cancer in May.

I wrote an essay about "returning to reading," and it was published by the literary blog Numero Cinq in July.

Other books I read over the summer:

- Off Book by Mark Sampson

- Hamlet by Shakespeare

- Fathers and Sons by Turgenev

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

- Flaubert in Egypt by Gustave Flaubert

- The Victim by Saul Bellow

- Widower's House: A Study in Bereavement (or how Margot and Mella forced me to flee my home) by John Bayley

I'm also poking my way through:

- A Tramp Abroad by Mark Twain

- Essays and Aphorisms by Arthur Schopenhaur

- Sentimental Education by Gustave Flaubert

- This Side Jordan by Margaret Laurence

- Saints of Big Harbour by Lynn Coady

- Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

- Long, Last, Happy by Barry Hannah

Do you see a pattern? I don't see a pattern.

Some of these books are works I've "meant to get to" and now find myself seeking out. Some I've picked up in used book shops. Others have been on a shelf in my house, ignored.

There's a lot of ribald reveling in the oddity of humanity in the above, but there's also some earthy earnestness.

I found in Turgenev cynicism that was starkly contemporary, and in Huck Finn's Mississippi adventure a freakishness consistent with the current U.S. election cycle.

I felt Hamlet's pain as my own, and, like Sampson's protagonist, remembered how wild and liberating the internet seemed in the 1990s.

Bellow's early novel contains both his trademark singing souls and bureaucratic absurdity of a Beckettean order.

But Flaubert in Egypt? Twain in Germany? Alien and eccentric. The diversity of human weirdness is duly noted.

Schopenhaur? I read the first paragraph and laughed. Likely not what he intended, but there is a dark humour there that I've seen before and like. I went to Schopenhaur after reading The Pugilist at Rest by Thom Jones. Schopenhaur is referenced throughout that book, and I was curious for more. The introduction compares Schopenhaur to "our own great pessimist" (Shakespeare), and I hadn't thought of the Bard that way before. I'd thought of him as a poet of chaos (like Bob Dylan). But pessimist? Hmm.

A Sentimental Education I'm drawn to, I think, because it's other worldly. Most of my life I've felt more akin with 20th century literature and not much desire about the 19th century so-called masters. But this summer that has changed. The contemporary has become fraught and I want to read the back catalog.

Early Margaret Laurence, set in Africa. Curious. Barry Hannah, the selected. Wild and wonderful. Lynn Coady just because I haven't got around to that one yet.

I started my essay on Woolf and Beckett without a voice, or with the most meager of voices, and with the faintest of ears. I was only getting one frequency, and I couldn't make out the full signal.

I can hear more now. I can speak more now. But the world is different. There has been a break from the past that will never heal. Beauty, however, remains, and much else. A deeper recognition of the mixed-up-ness of everything. A recognition that there is no resolution, no end to the storytelling.

The mighty river of literature just rolls on and on.

Monday, August 6, 2012

Widower's House

by John Bayley

W.W. Norton, 2001

Deep in his narrative, John Bayley confides: "The bereaved should maintain at all costs the privacy and, in their own eyes, the singularity of their status. A privilege not to be transgressed."

Following a section break, he continues: "I might have been feeling more and more desperate but I was also getting more and more pompous."

Pages later he writes: "Being a widower had turned me into a monster of egoism."

The back cover proclaims: "A book to be given to anyone dealing with the catastrophic loss of a loved one."

Having recently suffered the catastrophic loss of a loved one (my wife), I disagree.

I disagree with the subtitle. This is not a study in bereavement. It's a study in John Bayley's bereavement, and not really that either. It's well told, written by a highly intelligent and clever man, who is able to generate significant narrative frisson by taking a passive approach to his situation.

Forced to flee? Even Bayley knows that's not true. He ran away. Not a strategy he recommends, no, but not either a strategy outside his character.

But these be quibbles.

I started with the chosen quotations above, because they capture something essential about the experience of catastrophic loss. Nobody else has the slightest idea what you are experiencing. Each grief is unique. You are alone, and there is no vocabulary for your experience before you find it for yourself. The uniqueness of your experience can make you a bore. Time to move on, isn't it? Nice to have you back. Move along now. Not sure what happened to your over in your little wonderland, but, chip, chip, tally ho, and all that.

Yes, the risk is you become a "monster of egoism," kind of like Hamlet.

Bayley neatly escapes that fate, turning a passive aggressive retreat into a premeditated conquest. He escapes the tragic ending by seizing the day. Good for him. And good for the book. The ending comes wrapped in a bow.

Part of my problem, of course, is that I'm 43 and suffered my loss in mid-life, and Bayley is a retired Oxford professor. I won't say that he doesn't need to worry about what to do with the rest of his life, but it's of a different scale now, isn't it? He's also without children, so can suffer his egoism without incurring too much penalty. For himself and (non-existent) others.

I had the same problem with a book I read this past Spring, which was about caregiving. The book was loaned to me, and I can't remember the title now, but some of it was excellent, and some of it was shite.

The excellent part was about giving in to the ego of the person who needs care. Let go. Do what they want. Make them comfortable. That's all that matters. Resolve your conflicts in their favour.

Yes, yes, yes.

The shite part (for me) were examples of geriatric couples who were struggling with the fact that one of them couldn't do what s/he had used to be able to do before.

Once you've passed 70, I wanted to yell, what did you expect? This, to me, is unaccountable egoism. That you would think you could reach old age and not have to face death.

Perhaps I'm being unfair. Perhaps it's unrealistic to expect oldsters to be courageous. But, no, I don't believe so. I've known plenty of elderly with courage, and plenty of young without.

Perhaps this is what bothers me about Bayley's fleeing. He was heroic in caring for his dying wife, then he flees his house instead of informing a trespassing female that she needs to leave.

But it's the grief, of course. He's bereaved. He doesn't have the spine at the moment to do it.

Okay, I surrender. Life is hard. It's full of challenges. We can't surmount them all.

But existence precedes essence. You are what you do.

Sunday, August 5, 2012

Hamlet

I recently re-read Hamlet and also T.S. Eliot's essay on Shakespeare's play.

A choice quotation from that essay: "So far from being Shakespeare's masterpiece, the play is most certainly an artistic failure."

I cannot agree with that. Also, where the play rests within the hierarchy of Shakespeare's works doesn't interest me.

I was drawn to Hamlet, the character, because of the recent death of my wife. She died in May. I found myself ruminating on the Danish Prince and dug the play off my bookshelf. Only then did I realize why. The man is grieving.

Thus the artistic "problem" of the play. Called repeated to avenge the murder of his father, the King, Hamlet instead ruminates and delays.

Eliot: "We must simply admit that here Shakespeare tackled a problem which proved too much for him. Why he attempted it at all is an insoluble puzzle; under compulsion of what experience he attempted to express the inexpressibly horrible, we cannot ever know."

This is fine and true enough. However, Hamlet's deep plunges into his existential angst appear to tickle Eliot not at all.

Hamlet makes is directly clear what the problem is, "To be or not to be." This is often paraphrased, "On what grounds do I have to act?"

But Hamlet has no fear of action. He is decisive in escaping the pirates and re-writing the King's command, to cite one example. He is also well trained in swordsmanship and a well admired heir to the throne.

So why does he pause? What prevents him from taking his father's revenge?

I offer a small, personal reflection, based on the fact that I am about the same distance from my wife's death and Hamlet was from his father's, and that is this: the world is torn asunder and all one desires is a calm port.

Grief takes you away from yourself, and you need to constitute a new identity. A subconscious recognition of this is what drew me to re-read the play, I believe.

Hamlet could claim his rightful thrown and banish his confusion by killing his uncle, that is true, but the play, then, would not be a tragedy. If he acted quickly, it wouldn't even get us through the first act.

What we have instead is a meditation on existence that is of the first rank. Eliot, methinks, is mistaken.

Hamlet is too lost to constitute a new identity in the time available to him. He is overwhelmed and only too aware of the fragility of his own state.

Perhaps it's true that he enjoyed his walk on the dark side too much. Perhaps the sirens call him too strongly, and he cannot pull away. Because part of grief is a process of reflection and insight. Or it can be, if one lets it, and it can be overwhelming if one doesn't assert some control over it.

But grief overwhelms. It's what it does. And then one seeks again the surface.

Eliot cannot fathom Hamlet's dis-ease. From where I stand, Hamlet's problem is common.

A choice quotation from that essay: "So far from being Shakespeare's masterpiece, the play is most certainly an artistic failure."

I cannot agree with that. Also, where the play rests within the hierarchy of Shakespeare's works doesn't interest me.

I was drawn to Hamlet, the character, because of the recent death of my wife. She died in May. I found myself ruminating on the Danish Prince and dug the play off my bookshelf. Only then did I realize why. The man is grieving.

Thus the artistic "problem" of the play. Called repeated to avenge the murder of his father, the King, Hamlet instead ruminates and delays.

Eliot: "We must simply admit that here Shakespeare tackled a problem which proved too much for him. Why he attempted it at all is an insoluble puzzle; under compulsion of what experience he attempted to express the inexpressibly horrible, we cannot ever know."

This is fine and true enough. However, Hamlet's deep plunges into his existential angst appear to tickle Eliot not at all.

Hamlet makes is directly clear what the problem is, "To be or not to be." This is often paraphrased, "On what grounds do I have to act?"

But Hamlet has no fear of action. He is decisive in escaping the pirates and re-writing the King's command, to cite one example. He is also well trained in swordsmanship and a well admired heir to the throne.

So why does he pause? What prevents him from taking his father's revenge?

I offer a small, personal reflection, based on the fact that I am about the same distance from my wife's death and Hamlet was from his father's, and that is this: the world is torn asunder and all one desires is a calm port.

Grief takes you away from yourself, and you need to constitute a new identity. A subconscious recognition of this is what drew me to re-read the play, I believe.

Hamlet could claim his rightful thrown and banish his confusion by killing his uncle, that is true, but the play, then, would not be a tragedy. If he acted quickly, it wouldn't even get us through the first act.

What we have instead is a meditation on existence that is of the first rank. Eliot, methinks, is mistaken.

Hamlet is too lost to constitute a new identity in the time available to him. He is overwhelmed and only too aware of the fragility of his own state.

Perhaps it's true that he enjoyed his walk on the dark side too much. Perhaps the sirens call him too strongly, and he cannot pull away. Because part of grief is a process of reflection and insight. Or it can be, if one lets it, and it can be overwhelming if one doesn't assert some control over it.

But grief overwhelms. It's what it does. And then one seeks again the surface.

Eliot cannot fathom Hamlet's dis-ease. From where I stand, Hamlet's problem is common.

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

Flaubert on the future

A couple of days ago I saw a replay of a CBC story about how India is trying to "count" its 1.2 billion people. Trying to give each one an official "identity."

It reminded me of something else I'd read recently, a quotation from Gustave Flaubert (from Flaubert in Egypt):

You won't believe that Max and I talk constantly about the future of society. For me it is almost certain that at some more or less distant time it will be regulated like a college. Teachers will be the law. Everyone will be in uniform. Humanity will no longer commit barbarisms as it writes its insipid theme, but -- what wretched style! What lack of form, of rhythm, of spirit!

For the past two months I have been dealing with the death-administration of my late-wife. I cannot tell you how insipid are the granular details of modern "identity." Just try cancelling a deceased person's Amazon account, for example. The great corporation initially sent me back a reply, asking if I was sure I wanted to cancel this account. If the account is cancelled, no more purchases will be possible.

What lack of form, of rhythm, of spirit!

Oh, great, uncounted masses in India. Live. Just live.

It reminded me of something else I'd read recently, a quotation from Gustave Flaubert (from Flaubert in Egypt):

You won't believe that Max and I talk constantly about the future of society. For me it is almost certain that at some more or less distant time it will be regulated like a college. Teachers will be the law. Everyone will be in uniform. Humanity will no longer commit barbarisms as it writes its insipid theme, but -- what wretched style! What lack of form, of rhythm, of spirit!

For the past two months I have been dealing with the death-administration of my late-wife. I cannot tell you how insipid are the granular details of modern "identity." Just try cancelling a deceased person's Amazon account, for example. The great corporation initially sent me back a reply, asking if I was sure I wanted to cancel this account. If the account is cancelled, no more purchases will be possible.

What lack of form, of rhythm, of spirit!

Oh, great, uncounted masses in India. Live. Just live.

Friday, July 27, 2012

Wait & Party

My essay on my attempt to start reading again after the death of my wife.

Kate O’Rourke, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett: Wait & Party

Published on Numero Cinq.

Kate O’Rourke, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett: Wait & Party

Published on Numero Cinq.

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Mrs. Dalloway

I noted today that my last post here was on May 8th. That was a day of rest. On May 9th, I went with my wife to her oncologist to find out if the news was going to be bad or worse.

It turned out to be worse, and on May 23 she passed away.

I have been unable, among other things, to read. But this past weekend I decided to read Kate's favourite novel, one I hadn't read before: Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf.

Here's what I found there (p. 105): "Beauty was everywhere."

That and much more. It's a novel, among other things, about a woman planning a party. How very Kate. I hear her on every page.

It turned out to be worse, and on May 23 she passed away.

I have been unable, among other things, to read. But this past weekend I decided to read Kate's favourite novel, one I hadn't read before: Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf.

Here's what I found there (p. 105): "Beauty was everywhere."

That and much more. It's a novel, among other things, about a woman planning a party. How very Kate. I hear her on every page.

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

I Heart Short Stories - Part 2

Inspecting the Vaults by Eric McCormack (Penguin 1987, 1993).

The 1993 edition includes the novella The Paradise Motel. It also includes a cover blurb from a Montreal Gazette review: "odd and unsettling ... murder, deformity and cruelty are treated as everyday occurrences."

McCormack taught contemporary literature at the University of Waterloo while I attended that institution in the late-1980s, early-1990s. I didn't take his course, but I sat in on a couple. He taught Raymond Carver, Borges, Donald Bartheme. None of whom I'd heard of before.

He was also known as the author of a freaky collection of short fiction, Inspecting the Vaults.

I read it after I left Waterloo, during a period when I trembled with desire to write decent short fiction. What was that even? What was a short story?

I remember one McCormack class when he described meeting a woman whose grandmother had sat on the knee of Thomas Hardy (if I remember correctly). "There's a direct line from this classroom to Thomas Hardy," he said. Then he went on to describe a Hardy novel as one that turned on a plot point: "she drank a cup of tea."

No such subtlety to the degree of manners in the curriculum of McCormack's class. Later, after I'd asked McCormack to read some of my budding short fiction, I mentioned the blurb on his book to him.

"But murder, deformity and cruelty are everyday occurrences," I said.

He nodded knowingly and made a clever comment.

Cleverness is what shines out of his stories. Pessimism, too, likely. More than a flirtation with the gothic. A deep knowledge of world literature and movements away from realism. A fantastical imagination.

An un-Canadian disinterest in earnestness.

Reading this book helped me to define for myself what was the essential "storyness" in a short story. It wasn't the movement of action within a plot. It wasn't a twist or surprise ending. It was a manipulation of language and an attempt at a new kind of see-ing.

A digging deeper past surfaces and a stark honesty to reveal what one felt.

Eric, thank you. I haven't forgotten.

The 1993 edition includes the novella The Paradise Motel. It also includes a cover blurb from a Montreal Gazette review: "odd and unsettling ... murder, deformity and cruelty are treated as everyday occurrences."

McCormack taught contemporary literature at the University of Waterloo while I attended that institution in the late-1980s, early-1990s. I didn't take his course, but I sat in on a couple. He taught Raymond Carver, Borges, Donald Bartheme. None of whom I'd heard of before.

He was also known as the author of a freaky collection of short fiction, Inspecting the Vaults.

I read it after I left Waterloo, during a period when I trembled with desire to write decent short fiction. What was that even? What was a short story?

I remember one McCormack class when he described meeting a woman whose grandmother had sat on the knee of Thomas Hardy (if I remember correctly). "There's a direct line from this classroom to Thomas Hardy," he said. Then he went on to describe a Hardy novel as one that turned on a plot point: "she drank a cup of tea."

No such subtlety to the degree of manners in the curriculum of McCormack's class. Later, after I'd asked McCormack to read some of my budding short fiction, I mentioned the blurb on his book to him.

"But murder, deformity and cruelty are everyday occurrences," I said.

He nodded knowingly and made a clever comment.

Cleverness is what shines out of his stories. Pessimism, too, likely. More than a flirtation with the gothic. A deep knowledge of world literature and movements away from realism. A fantastical imagination.

An un-Canadian disinterest in earnestness.

Reading this book helped me to define for myself what was the essential "storyness" in a short story. It wasn't the movement of action within a plot. It wasn't a twist or surprise ending. It was a manipulation of language and an attempt at a new kind of see-ing.

A digging deeper past surfaces and a stark honesty to reveal what one felt.

Eric, thank you. I haven't forgotten.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Monday, April 23, 2012

Derek Hayes

In his TDR interview, Derek Hayes describes the characters in his short story collection, The Maladjusted (Thistledown, 2011), as people "who suffer from anxiety or whose thinking is a bit distorted."

My Oxford Concise dictionary defines maladjusted as "(of a person) unable to adapt to or cope with the demands of a social environment."

Judged by that definition, Hayes' description of his book is bang on. This is not a noir collection of stories about people from the wrong side of the tracks or an exploration of marginal sub-cultures. These stories are character sketches of people who view reality through a prism slightly (or more) askew.

Now everyone's perspective is different, so what I'm trying to get at here is more than simply subjectivity. What Hayes' characters have, rather, is a self-awareness about their relationship with others and how a conflict within themselves prevents them from sharing common ground with others, or connecting deeply with others, or feeling "a part of it" (feeling apart from it), or being able to manage, per the dictionary definition, "the demands of a social environment."

Yes, there is a David Foster Wallace-ness to these stories, though Hayes' characters are more ... what should one say? Real? Less extremely different, perhaps?

The Maladjusted packs 16 stories into just over 200 pages. The stories also take place around the globe and the narrators speak a multitude of voices: different races, different genders, different ages, different intellectual and emotional capacities.

Anxiety knows no boundaries.

The diversity of the collection is abundant and rewarding, and the ease of the storytelling is deceptively simple, though the stories are often anything but.

A debut collection worth checking out.

My Oxford Concise dictionary defines maladjusted as "(of a person) unable to adapt to or cope with the demands of a social environment."

Judged by that definition, Hayes' description of his book is bang on. This is not a noir collection of stories about people from the wrong side of the tracks or an exploration of marginal sub-cultures. These stories are character sketches of people who view reality through a prism slightly (or more) askew.

Now everyone's perspective is different, so what I'm trying to get at here is more than simply subjectivity. What Hayes' characters have, rather, is a self-awareness about their relationship with others and how a conflict within themselves prevents them from sharing common ground with others, or connecting deeply with others, or feeling "a part of it" (feeling apart from it), or being able to manage, per the dictionary definition, "the demands of a social environment."

Yes, there is a David Foster Wallace-ness to these stories, though Hayes' characters are more ... what should one say? Real? Less extremely different, perhaps?

The Maladjusted packs 16 stories into just over 200 pages. The stories also take place around the globe and the narrators speak a multitude of voices: different races, different genders, different ages, different intellectual and emotional capacities.

Anxiety knows no boundaries.

The diversity of the collection is abundant and rewarding, and the ease of the storytelling is deceptively simple, though the stories are often anything but.

A debut collection worth checking out.

Sunday, April 15, 2012

I Heart Short Stories - Part 1

It all stared with Hemingway, with the self-conscious literariness of the short stories, with the iceberg comment, with show-don't-tell and A Clean, Well-Lighted Place and Hills Like White Elephants.

I was taken with the idea that the author could provide, say, 10 per cent of the story (the iceberg above water) and leave it up to the reader to fill in the rest. The story would be like a painting, requiring engaged interpretation, not simply an exposition stuffed with all possible details, which is what Dickens seemed to me, over-written nonsense.

Later, I would read in A Moveable Feast how Hemingway's style evolved from viewing the suggestive brush strokes of the Impressionists, and the circle of influence grew tighter. Impressionism is what I thought art should be. But then I was a teenager and listened to The Doors.

Break on through. Capture the small, essential granules of life.

Portray grace under pressure.

Over the years, I've tried to unwind Hemingway's influence on my reading habits. I've broadened and complicated my views of what a short story can be. I've noted the limits of the Hemingway style, how minimalism can be a trap, how the heroic, the depressive and the male ego mix in Hemingway in sometimes destructive ways.

But even after all of that, it's where I've chosen to start what I hope will be a series of reflections on different short story authors and books, a random flowering of opinion and fact.

When I first read Raymond Carver, Short Cuts, I saw how he had taken Hemingway, added some Kafka, and revealed new textures of storytelling. Story making. So Much Water So Close To Home, for example, has a title that sounds like Hemingway. The minimalist style forces the reader to interpret "what's missing" in order to make sense of the action, the story also critiques the male ego and introduces a female voice in a way Hemingway could never quite provide.

So Hemingway is still part of the foundation of my reading experience, but also I look for writers who can breakout of the perspective of the Hemingway experience and put their own stamp on "reality."

Which is something I'll get to later, the whole question of whether language can refer to anything other than itself and the struggle between the realists and fabulists. Which may not be a struggle at all, just different points on a storytelling spectrum with no contradiction inferred between them.

For now, though, I salute Hemingway and his declarative sentences. They are built to last.

Thursday, April 12, 2012

Short Story Reviews

Go to this page on the CBC website, then under "display" and "all genres" change that to "fiction-short."

And you will get a pretty good list of recent short fiction in Canada (from Quill & Quire reviews).

Cheers.

And you will get a pretty good list of recent short fiction in Canada (from Quill & Quire reviews).

Cheers.

Friday, April 6, 2012

Ralph Ellison and Fussing about the Novel

Hospital waiting rooms aren't good for much, but they are places to pick up miscellaneous magazines.

And so it happened that this week past I acquired a copy of the January 12, 2012 New York Times Magazine, which includes an article by Garth Risk Hallberg titled "Why Write Novels at All?"

The past few weeks I've also been reading Ralph Ellison's essay collection, Going to the Territory, and the recent issue (#84) of Canadian Notes & Queries, which contains much of interest, but the essay I'm going to reference here is by Patricia Robertson and called "Against Domesticated Fiction, or The Need for Re-enchantment."

I also see the Douglas Glover has added an online summary of DG sources on how to write a novel.

Personally, I have no idea how to write a novel, and I don't have a locked-in view that novels should be any one way or another. Except that they should not be simple; they should not be cliched; they should challenge the reader and provide evidence of an originality of style, voice, technique and/or point of view. We don't need novels that sound like other novels or stories that replicate other stories.

In The Art of the Novel, Milan Kundera argues that novels should do what only novels should do. That is, now that we have TV, movies, radio and a host of other media, what is special to the novel?

Ellison's view (from "The Novel as a Function of American Democracy") is that "the novel has always been tied up with the idea of nationhood. What are we? Who are we? What has the experience of the particular group been? How did it become this way? What is it that stopped us from attaining the ideal?"

On Henry James, Stephen Crane and Mark Twain, Ellison says, "In the works of these men ... the novel was never used merely as a medium of entertainment. These writers suggested possibilities, courses of action, stances against chaos." "The novel functioned beyond entertainment in helping create the American conception of America."

To Canadian readers, this mission might sound familiar; it might remind us of the nationalist mission of the 1970s, that the primary job of Canadian writers was to define Canada. That is, it might seem a corporate mission rather than an individual mandate.

However, Ellison is at pains to repeatedly stress that writers ought to position themselves within the tradition of great writing first and foremost, and they need to avoid the swamp of the sociological "we." Ellison tells us he took his inspiration from Joyce, Eliot and Pound (as well as Twain, Hemingway, and Emerson) and claimed the pluralistic culture of America as his own well spring.

Repeatedly, he says that Americans are both black and white, European and African, in their cultural influences and it is not race or blood that defines an individual's culture or talent. It is individual force of will and self-education of all of the best and broadest of all of the world's cultures. But, for him, there is also a signature document: The American Constitution. Ellison's narrative of the evolution of the novel is bound up with the 18th-century celebration of the individual and the break from the British Crown. It is also bound up in the failure of that promise in the form of ongoing slavery, leading to the Civil War, and then the failure of the Reconstruction.

Ellison's claim is that it is the novel's job to help America complete its promise, and assist the creation of a new consciousness of the individual beyond the boundaries of race, social class, or other cliches. His essays make for stirring reading, and they remain surprisingly contemporary. One might say that they even foreshadow Obama, and also the failure post-2008 of a post-racial cultural revolution to take hold.

In the NYT Magazine, Risk Hallberg writes about what he called the Franzen Generation and a literary conference in Italy in 2006 called Le Conservazioni, rich with YouTube links.

The Franzen Generation consists of Jonathan Franzen, Jeffrey Eugenides, Zadie Smith and David Foster Wallace, and their common element, says Risk Hallberg, is that these writers have made making us feel less alone the primary purpose of their fiction.

The focus, in other words, has become hyper-individual as the post-modern experiments have taken away our ability to agree on a common, stabilizing reality.

Risk Hallberg concludes that this approach "won't quite be enough" to ensure that "art is to endure."

Patricia Robertson's excellent essay also plays for high stakes, and she also identifies what she calls a "downward and inward trend of contemporary fiction."She quotes Janet Burroway:

The history of Western literature shows a movement downward through society from royalty to gentry to the middle classes to the lower classes to the dropouts; inward from heroic action to social drama to individual consciousness to the subconscious to the unconscious.

And the problem, says Robertson, is that "we have nowhere further to go."

At this point, I hear Ellison harking back to 1776 and the documents of the Founding Fathers. There were promises stated there that remain unfulfilled. There is an unfinished revolution that is still ripe with narrative. The financial collapse of 2008, for example, writ large the failure of American capitalism to deliver on the promise of a perpetually renewing middle-class dream. The poor got poorer and some of the rich went bankrupt, but very quickly the political and economic elites rushed not to fix the system, but return it to the status quo as much as possible.

Going forward, the crash of 2008 may affect more lives and be a more defining early-21st century moment than even 9/11. And we need our writers to grasp that.

Patterson echoes some of Ellison's moral vision. She calls on writers to "revivify old forms by using our imaginations in the service of new stories. In doing so," she says, "we will reclaim the essential role of the storyteller, the one who reminds us who we are and where we came from, and who restores the world through authentic story."

Actually, that sounds a lot like Ellison, doesn't it?

I look forward to reading the novel about Fort McMurray, Alberta. That's an epic awaiting its Balzac.

And so it happened that this week past I acquired a copy of the January 12, 2012 New York Times Magazine, which includes an article by Garth Risk Hallberg titled "Why Write Novels at All?"

The past few weeks I've also been reading Ralph Ellison's essay collection, Going to the Territory, and the recent issue (#84) of Canadian Notes & Queries, which contains much of interest, but the essay I'm going to reference here is by Patricia Robertson and called "Against Domesticated Fiction, or The Need for Re-enchantment."

I also see the Douglas Glover has added an online summary of DG sources on how to write a novel.

Personally, I have no idea how to write a novel, and I don't have a locked-in view that novels should be any one way or another. Except that they should not be simple; they should not be cliched; they should challenge the reader and provide evidence of an originality of style, voice, technique and/or point of view. We don't need novels that sound like other novels or stories that replicate other stories.

In The Art of the Novel, Milan Kundera argues that novels should do what only novels should do. That is, now that we have TV, movies, radio and a host of other media, what is special to the novel?

Ellison's view (from "The Novel as a Function of American Democracy") is that "the novel has always been tied up with the idea of nationhood. What are we? Who are we? What has the experience of the particular group been? How did it become this way? What is it that stopped us from attaining the ideal?"

On Henry James, Stephen Crane and Mark Twain, Ellison says, "In the works of these men ... the novel was never used merely as a medium of entertainment. These writers suggested possibilities, courses of action, stances against chaos." "The novel functioned beyond entertainment in helping create the American conception of America."

To Canadian readers, this mission might sound familiar; it might remind us of the nationalist mission of the 1970s, that the primary job of Canadian writers was to define Canada. That is, it might seem a corporate mission rather than an individual mandate.

However, Ellison is at pains to repeatedly stress that writers ought to position themselves within the tradition of great writing first and foremost, and they need to avoid the swamp of the sociological "we." Ellison tells us he took his inspiration from Joyce, Eliot and Pound (as well as Twain, Hemingway, and Emerson) and claimed the pluralistic culture of America as his own well spring.

Repeatedly, he says that Americans are both black and white, European and African, in their cultural influences and it is not race or blood that defines an individual's culture or talent. It is individual force of will and self-education of all of the best and broadest of all of the world's cultures. But, for him, there is also a signature document: The American Constitution. Ellison's narrative of the evolution of the novel is bound up with the 18th-century celebration of the individual and the break from the British Crown. It is also bound up in the failure of that promise in the form of ongoing slavery, leading to the Civil War, and then the failure of the Reconstruction.

Ellison's claim is that it is the novel's job to help America complete its promise, and assist the creation of a new consciousness of the individual beyond the boundaries of race, social class, or other cliches. His essays make for stirring reading, and they remain surprisingly contemporary. One might say that they even foreshadow Obama, and also the failure post-2008 of a post-racial cultural revolution to take hold.

In the NYT Magazine, Risk Hallberg writes about what he called the Franzen Generation and a literary conference in Italy in 2006 called Le Conservazioni, rich with YouTube links.

The Franzen Generation consists of Jonathan Franzen, Jeffrey Eugenides, Zadie Smith and David Foster Wallace, and their common element, says Risk Hallberg, is that these writers have made making us feel less alone the primary purpose of their fiction.

The focus, in other words, has become hyper-individual as the post-modern experiments have taken away our ability to agree on a common, stabilizing reality.

Risk Hallberg concludes that this approach "won't quite be enough" to ensure that "art is to endure."

Patricia Robertson's excellent essay also plays for high stakes, and she also identifies what she calls a "downward and inward trend of contemporary fiction."She quotes Janet Burroway:

The history of Western literature shows a movement downward through society from royalty to gentry to the middle classes to the lower classes to the dropouts; inward from heroic action to social drama to individual consciousness to the subconscious to the unconscious.

And the problem, says Robertson, is that "we have nowhere further to go."

At this point, I hear Ellison harking back to 1776 and the documents of the Founding Fathers. There were promises stated there that remain unfulfilled. There is an unfinished revolution that is still ripe with narrative. The financial collapse of 2008, for example, writ large the failure of American capitalism to deliver on the promise of a perpetually renewing middle-class dream. The poor got poorer and some of the rich went bankrupt, but very quickly the political and economic elites rushed not to fix the system, but return it to the status quo as much as possible.

Going forward, the crash of 2008 may affect more lives and be a more defining early-21st century moment than even 9/11. And we need our writers to grasp that.

Patterson echoes some of Ellison's moral vision. She calls on writers to "revivify old forms by using our imaginations in the service of new stories. In doing so," she says, "we will reclaim the essential role of the storyteller, the one who reminds us who we are and where we came from, and who restores the world through authentic story."

Actually, that sounds a lot like Ellison, doesn't it?

I look forward to reading the novel about Fort McMurray, Alberta. That's an epic awaiting its Balzac.

Saturday, March 17, 2012

Russell Wangersky & the Pros/Cons of Realism

Mark Anthony Jarman has a review of Russell Wangersky's new short story collection, Whirl Away (Thomas Allen, 2012), in today's Globe & Mail.

Mark Anthony Jarman has a review of Russell Wangersky's new short story collection, Whirl Away (Thomas Allen, 2012), in today's Globe & Mail.It's a fine review and an excellent summary of the book, which I have just finished reading.

Like Cheever or Munro, Russell Wangersky delves stealthily into disquieting corners of the domestic sphere, his stories dissecting lives when they are fracturing, lives at stress points, lives much like the roller coaster at the centre of McNally's Fair, an exciting and popular ride gleaming with fresh paint, but about to collapse from hidden rust and broken bolts. Such parallels are his métier and meat as a stylist. Water stains on a wall mirror flaws in the soul (daub on some paint and get rid of the place), and a meal at a diner resembles a relationship, “resolute about not living up to its promise.”

Whirl Away is a fine example of the kind of literary realism that is often mistaken as a Canadian canonical model. Munro is the prime influence here (in Canada, I mean); Jarman is right to also cite Cheever as an international icon of this approach to short fiction.

Interestingly, Jarman's own work is product of a tradition that deviates from soft-focus realism, following a path into wilder literary terrain, territory often said to have been mapped initially (or most prominently recently) by Barry Hannah. See, for example, Airships (1978).

For an idea of how contentious the dispute between these short story "camps" can be, see 2008's Salon des Refuses.

My intention here is not to fling Whirl Away into one camp or the other, or to prioritize one approach to short fiction over the other (there are a large multiple of approaches, and they are all legitimate). All that I intend here is to use this introduction to jump at a tangent to a question that animates me from time to time.

Wither realism?

We are well past McLuhan, and well along into a world of "socially mediated" lives. We are also well past the post-modern moment and deep into a world where we not only live our lives, but also simultaneously and self-consciously reflect, tweet, post, talk about, ironize and re-contextualize them, ad nauseum. If there was ever, there is now not ... any there, there.

As a reader, I felt anxiety reading Whirl Away, a feeling I also had when I read Alex McLeod's Light Lifting and Sarah Selecky's This Cake is for the Party. Both, by the way, excellent.

As a reader, I distrust realism. I want to crack its surfaces and break it up, interrogate its assumptions, like a Cindy Sherman photograph.

Which doesn't mean I dislike realism. But, if I'm honest, it kind of pisses me off.

And I'm not sure why.

Though it's connected to the pleasure I take in stuff like Zsuzsi Gartner's Better Living Through Plastic Explosives. Gartner's break with realism couldn't be clearer.

Food for thought.

Thursday, March 15, 2012

On Reading & Reviewing

Literary fiction consists of story and manner. That is, the same story (plot) can be told any number of ways. As Wallace Stevens reminded us, there are 13 ways of looking at a black bird, and many more multiple ways of writing fiction.

This is, of course, an over-simplification, but sharing any interpretation requires it.

Are some manners of fiction better than others? I can't say that this is so, except that surely some manners are worse than others.

Some are more niave and some are more complex, and as literary readers, it's the complexity we crave. Yes?

Not always. In fact, in my experience, rarely.

However the reading process works, it is subjective above all. You look at the black bird one way, and I see it another. Do we have any chance of understanding each other? Can we ever read the same book?

What can the book reviewer hope to accomplish?

In the past, I have answered this question (for myself) by trying to convey in my reviews a clear articulation of my response to the book ... to back up that response with quotations from the text. If someone has a difference response to the book, then they can at least see the "evidence" behind my conclusion.

Lately, I haven't written any reviews. Not even on this blog. I'm feeling an existential drift. In writing these blog posts, am I speaking only to myself? (If so, that hasn't been a problem in the past. Often, just the process of writing the review enabled me to understand more deeply my response to the book.)

Also, I've realized that my response(s) to book(s) are multiple. Not only do I not evalulate books by a thumbs-up, thumbs-down principle, but I also recognized that I have contradictory conclusions about many books. In fact, these are the complex books that I (say I) crave.

Andre Alexis's Beauty & Sadness was one such book. There are many others.

In writing reviews, how do I capture this multiplicity of thoughts? This rainbow of responses? We are taught to write an essay with a strong central thesis and back it up, bang, pow, smash, with confidence.

Is multiplicity not just wishy-washy-ness?

A recent post on Lemon Hound also addresses this conundrum.

First linking to Constant Critic, Sina Queryas then comments on why she likes that website:

...there is such a diversity of vision and style here and you know, I don't want to know what a reviewer is going to think about a book before I start reading a review....though I do want to know that there will be a consistent kind of looking, or an integrity of vision even if I don't agree with the reviewer, and that, she said, was her objective: consistent reviews.

Diversity and unity, engaged perpetually in the act of criticism, a revolution (spinning) of thought, never settled, yet always seeking coherence.

This blog attempts a spinning of opinions by providing links to other Canlit blogs, reinforcing that there is no single point of contact for any reader (or ought not to be).

And I attempt to write spinny reviews, that offer argument, and also, hopefully, open multiple avenues for (re)interpretation.

Interpretation as breath, as act of living, as unending.

A thought that intrigues me.

This is, of course, an over-simplification, but sharing any interpretation requires it.

Are some manners of fiction better than others? I can't say that this is so, except that surely some manners are worse than others.

Some are more niave and some are more complex, and as literary readers, it's the complexity we crave. Yes?

Not always. In fact, in my experience, rarely.

However the reading process works, it is subjective above all. You look at the black bird one way, and I see it another. Do we have any chance of understanding each other? Can we ever read the same book?

What can the book reviewer hope to accomplish?

In the past, I have answered this question (for myself) by trying to convey in my reviews a clear articulation of my response to the book ... to back up that response with quotations from the text. If someone has a difference response to the book, then they can at least see the "evidence" behind my conclusion.

Lately, I haven't written any reviews. Not even on this blog. I'm feeling an existential drift. In writing these blog posts, am I speaking only to myself? (If so, that hasn't been a problem in the past. Often, just the process of writing the review enabled me to understand more deeply my response to the book.)

Also, I've realized that my response(s) to book(s) are multiple. Not only do I not evalulate books by a thumbs-up, thumbs-down principle, but I also recognized that I have contradictory conclusions about many books. In fact, these are the complex books that I (say I) crave.

Andre Alexis's Beauty & Sadness was one such book. There are many others.

In writing reviews, how do I capture this multiplicity of thoughts? This rainbow of responses? We are taught to write an essay with a strong central thesis and back it up, bang, pow, smash, with confidence.

Is multiplicity not just wishy-washy-ness?

A recent post on Lemon Hound also addresses this conundrum.

First linking to Constant Critic, Sina Queryas then comments on why she likes that website:

...there is such a diversity of vision and style here and you know, I don't want to know what a reviewer is going to think about a book before I start reading a review....though I do want to know that there will be a consistent kind of looking, or an integrity of vision even if I don't agree with the reviewer, and that, she said, was her objective: consistent reviews.

Diversity and unity, engaged perpetually in the act of criticism, a revolution (spinning) of thought, never settled, yet always seeking coherence.

This blog attempts a spinning of opinions by providing links to other Canlit blogs, reinforcing that there is no single point of contact for any reader (or ought not to be).

And I attempt to write spinny reviews, that offer argument, and also, hopefully, open multiple avenues for (re)interpretation.

Interpretation as breath, as act of living, as unending.

A thought that intrigues me.

Thursday, February 2, 2012

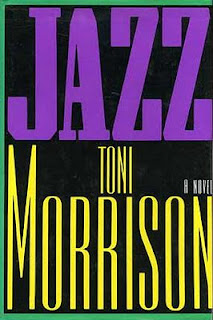

Toni Morrison

Of course, later she would win the Nobel and top the NY Times list of "most prominent" novelists, 1980-2005.

I saw her read at Trinity St. Paul's United Church in (I think) 1997 (what fantastic hair!) and walking out afterwards overheard two women:

"You know from a feminist point of view she's interesting."

"Why's that?"

"She doesn't just present women as victims."

*

[This review first appeared in Imprint, University of Waterloo, June 26, 1992]

Jazz

by Toni Morrison

Knopf, 1992

Sth, I know that woman. She used to live with a flock of birds on Lenox Aveune. Know her husband, too. He fell for an eighteen-year-old girl with one of those deepdown, spooky loves that made him so sad and happy he shot her just to keep the feeling going.

There is a school of literary criticism that holds to the belief that black women writers are doubly discriminated against in their quest for intellectual recognition. They are, it is said, excluded from the discussions that determine academic excellence first because women's experiences are generally devalued in our culture, and second because white people simply don't try hard enough to understand black people.

Toni Morrison is one of the few writers, along with Alice Walker, to have broken through this cultural barrier. She won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for her novel Beloved and has just released Jazz to somewhat confused critical acclaim. Affirming the notion that institutions of power are unable to understand marginal voices, Time magazine's review of Jazz praised Morrison's literary ability while confessing not to understand her purpose.

The novel's plot is contained in its first sentences, quoted above. Simply put, the novel is about a couple who grow apart as they grow old. He takes a young lover, who leaves him. He kills his lover. Life goes on, somewhat like before. But also radically different. The novel concentrates on its characters, not its plot. It tells us in deeply drawn strokes each individual's quirks and fantasies, and after a while it is difficult to discern the victims from the offenders. Everyone is hurting, everyone is looking for redemption.

Likely this is not what you'd expect from a novel about a love triangle and a murder. But Morrison's point is that there are not easy answers, the roots of the problem run deep. The symptoms may be obvious, but the causes are certainly not. Jazz explores (as a Charlie Parker solo explores; it wanders, but always to the right place) the depth of this theme, celebrating human connections at the same time as it points out the consequences of their failings.

Love's connections may be frail, Morrison is saying, and they are often the cause of much pain and anguish, but they are also life's strongest bonds. Jazz plays with this paradox. The purpose of the novel, then, is simple. Jazz is jazz. That is all. Nothing more, nothing less. And as Louis Armstrong once said, "If you have to ask what's jazz, you'll never know."

As a cultural phenomena, the novel deserves to be discussed within the context of contemporary race and gender relations. A novel about black people in Harlem in the 1920s, Jazz speaks the voices of the marginalized people who feel they've moved up in the world. The readers, however, who know how hollow these dreams of 70 years ago are, can see the tragedy in the characters' ambitions. Just as they can see how little has changed with regards to violence against women.

But Jazz is not an overtly political novel, though in a completely subversive way the novel points out the commonalities that bind all people. These are the connections of emotion, the need to be loved, understood and wanted. And though these connections function on the level of individuals, they are also symptomatic of our culture as a whole.

Says one character: "All kinds of white people are there. Two kinds. The ones that feel sorry for you and the ones that don't. And both amount to the same thing. Nowhere in between is respect."

I saw her read at Trinity St. Paul's United Church in (I think) 1997 (what fantastic hair!) and walking out afterwards overheard two women:

"You know from a feminist point of view she's interesting."

"Why's that?"

"She doesn't just present women as victims."

*

[This review first appeared in Imprint, University of Waterloo, June 26, 1992]

Jazz

by Toni Morrison

Knopf, 1992

Sth, I know that woman. She used to live with a flock of birds on Lenox Aveune. Know her husband, too. He fell for an eighteen-year-old girl with one of those deepdown, spooky loves that made him so sad and happy he shot her just to keep the feeling going.

There is a school of literary criticism that holds to the belief that black women writers are doubly discriminated against in their quest for intellectual recognition. They are, it is said, excluded from the discussions that determine academic excellence first because women's experiences are generally devalued in our culture, and second because white people simply don't try hard enough to understand black people.

Toni Morrison is one of the few writers, along with Alice Walker, to have broken through this cultural barrier. She won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for her novel Beloved and has just released Jazz to somewhat confused critical acclaim. Affirming the notion that institutions of power are unable to understand marginal voices, Time magazine's review of Jazz praised Morrison's literary ability while confessing not to understand her purpose.

The novel's plot is contained in its first sentences, quoted above. Simply put, the novel is about a couple who grow apart as they grow old. He takes a young lover, who leaves him. He kills his lover. Life goes on, somewhat like before. But also radically different. The novel concentrates on its characters, not its plot. It tells us in deeply drawn strokes each individual's quirks and fantasies, and after a while it is difficult to discern the victims from the offenders. Everyone is hurting, everyone is looking for redemption.

Likely this is not what you'd expect from a novel about a love triangle and a murder. But Morrison's point is that there are not easy answers, the roots of the problem run deep. The symptoms may be obvious, but the causes are certainly not. Jazz explores (as a Charlie Parker solo explores; it wanders, but always to the right place) the depth of this theme, celebrating human connections at the same time as it points out the consequences of their failings.

Love's connections may be frail, Morrison is saying, and they are often the cause of much pain and anguish, but they are also life's strongest bonds. Jazz plays with this paradox. The purpose of the novel, then, is simple. Jazz is jazz. That is all. Nothing more, nothing less. And as Louis Armstrong once said, "If you have to ask what's jazz, you'll never know."

As a cultural phenomena, the novel deserves to be discussed within the context of contemporary race and gender relations. A novel about black people in Harlem in the 1920s, Jazz speaks the voices of the marginalized people who feel they've moved up in the world. The readers, however, who know how hollow these dreams of 70 years ago are, can see the tragedy in the characters' ambitions. Just as they can see how little has changed with regards to violence against women.

But Jazz is not an overtly political novel, though in a completely subversive way the novel points out the commonalities that bind all people. These are the connections of emotion, the need to be loved, understood and wanted. And though these connections function on the level of individuals, they are also symptomatic of our culture as a whole.

Says one character: "All kinds of white people are there. Two kinds. The ones that feel sorry for you and the ones that don't. And both amount to the same thing. Nowhere in between is respect."

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Elizabeth Smart

Google Elizabeth Smart today and you get the teenage kidnap victim. But there was another Elizabeth Smart whose story is at least as interesting and quite divergently different.

*

By Heart: Elizabeth Smart, A Life

by Rosemary Sullivan

Penguin, 1992

[This review first appeared in Imprint, University of Waterloo, May 29, 1992]

Once upon a time there was a woman who was just like all women. And she married a man who was just like all men. And they had some children who were just like all children. And it rained all day. ... In the end the died. Do you insist on vulgar details? Mere gossip? Loathsome gluttony? Chapter one: they were born. Chapter two: they were bewildered. Chapter three: they loved. Chapter four: they suffered. Chapter five: they were pacified. Chapter six: they died. -- Elizabeth Smart

Elizabeth Smart wrote the poetic-prose masterpiece, By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, and may just be Canada's greatest and most misunderstood writer. I mean, The Globe's Jay Scott somehow found it fit to describe her in last March's Chatelaine magazine as "the bisexual bohemian product of a wealthy Ottawa family against whom she rebelled."

Smart, says Scott, "carried on a passionately masochistic relationship with married poet George Barker for 19 years; she even bore him four children." Even, says Scott. It makes you wonder if he even bothered to read By Heart, "the awkwardly written but superbly researched biography" he was supposedly reviewing. What an idiot. What a country.

Elizabeth Smart once described Canada as a majestic country without any people in it, by which she meant there weren't any decent Canadian poets. For Smart, there weren't any people but poets, which was why she had four kids by T.S. Eliot's protoge, George Barker, though they hardly ever lived together and her four children were only four of his fifteen.

Smart wrote By Grand Central Station about the initial stages of her relationship with Barker, when he was drifting between Smart and his wife, manipulating them both and putting down his carelessness to the cause of Art. First published during World War II, the book was well received but quickly vanished. Its powerful poetry only resurfaced to prominence later with the rise of interest in women writers and a democratic reshuffling of the literary canon. Smart's work now stands as one of the pinnacles of poetic-prose of the 20th century.

In her own way, Smart, then, is a transitional figure. Hugely passionate and yet fiercely independent, she embodies both the traditional female mother-archetype and the contemporary feminist-ideal. She had four children because she wanted children. She was obsessed with them all her life. When she read George Barker's poetry in a book store one day, she decided he would be the father of her children -- damn the powers that be -- and he was. In that way, she was what her generation of told her a woman should be.

But she was also a New Woman, a female writer, a romantic, who wanted to live a life like Byron's. She wanted to live her life with kinetic energy, fight against the forces that would try to hold her back, struggle against the suffering, and win. Of James Bond she once wrote that he could have his mistresses as long as she could have her lovers. Society was hypocritical: it praised adventurous men but damned adventurous women.

...

Reading at Seagram's Museum on May 6, Sullivan expounded on her thesis that Smart had two primary themes in her writing, love and silence. Smart first pursued George Barker with an obsessiveness that was total and blinding, believing as she did that heroic love would save her from her bland, bourgeois, Canadian up-bringing.

But finding her vision far less than realistic, Smart then turned later in life, like many creative women of her generation (Sylivia Plath comes easily to mind), to trying to find a voice for all the women who are silenced by a culture that dominates and subjugates them.

Smart came from a wealthy family, but she spent the prime of her life as a single mother struggling to make ends meet, dying all the time only to write. She knew only too well what she came to call "woman's lot." Smart's second book, The Assumptions of Rogues and Rascals, illuminates her second theme. She "rebelled" (said Scott)? Good God, I hope so.

At one point in By Heart, Sullivan poses the rhetorical question, How then do you survive life's script? "By a rage of will," she says and quotes Smart:

Like this: pray; bang your head; be beautiful; wait; love; rage; rail; look, and possibly, if lucky, see; love again; try to stop loving; go on loving; bustle about; rush to and fro. Whatever you say will be far less than the truth.

"Refuse dismay and battle on regardless," says Sullivan, "which is what Elizabeth did. Indeed, Elizabeth believed the only response to life was 'ecstatic surrender' since life has a will stronger than yours. 'It is not for you to know.' She would always ask herself, 'Can't I possibly be a little braver?'"

Elizabeth Smart, says Sullivan, "lived on a vertical plane, where ecstasy or pain could deliver themselves like shafts shattering the moment." And -- oh! -- she is so sad! Her language has such strength and yet she was so subsumed by her need to love and be loved. She couldn't believe she was a good writer until a man told her she was. But not just any man, a poet. Barker, thankfully, gave her that praise, and Smart gave us her prose.

So full of contradictions, it is difficult to know what to make of Smart's life in our contemporary context. Her absolute devotion to her children might be seen as an attack on women's progress in the workplace, and yet Smart broke through many -- if not all -- of the social taboos of her day (and these days, too). That she is a great writer is gospel. Her life will only grow in significance. Rosemary Sullivan has done her well.

*

By Heart: Elizabeth Smart, A Life

by Rosemary Sullivan

Penguin, 1992

[This review first appeared in Imprint, University of Waterloo, May 29, 1992]

Once upon a time there was a woman who was just like all women. And she married a man who was just like all men. And they had some children who were just like all children. And it rained all day. ... In the end the died. Do you insist on vulgar details? Mere gossip? Loathsome gluttony? Chapter one: they were born. Chapter two: they were bewildered. Chapter three: they loved. Chapter four: they suffered. Chapter five: they were pacified. Chapter six: they died. -- Elizabeth Smart

Elizabeth Smart wrote the poetic-prose masterpiece, By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept, and may just be Canada's greatest and most misunderstood writer. I mean, The Globe's Jay Scott somehow found it fit to describe her in last March's Chatelaine magazine as "the bisexual bohemian product of a wealthy Ottawa family against whom she rebelled."

Smart, says Scott, "carried on a passionately masochistic relationship with married poet George Barker for 19 years; she even bore him four children." Even, says Scott. It makes you wonder if he even bothered to read By Heart, "the awkwardly written but superbly researched biography" he was supposedly reviewing. What an idiot. What a country.

Elizabeth Smart once described Canada as a majestic country without any people in it, by which she meant there weren't any decent Canadian poets. For Smart, there weren't any people but poets, which was why she had four kids by T.S. Eliot's protoge, George Barker, though they hardly ever lived together and her four children were only four of his fifteen.

Smart wrote By Grand Central Station about the initial stages of her relationship with Barker, when he was drifting between Smart and his wife, manipulating them both and putting down his carelessness to the cause of Art. First published during World War II, the book was well received but quickly vanished. Its powerful poetry only resurfaced to prominence later with the rise of interest in women writers and a democratic reshuffling of the literary canon. Smart's work now stands as one of the pinnacles of poetic-prose of the 20th century.

In her own way, Smart, then, is a transitional figure. Hugely passionate and yet fiercely independent, she embodies both the traditional female mother-archetype and the contemporary feminist-ideal. She had four children because she wanted children. She was obsessed with them all her life. When she read George Barker's poetry in a book store one day, she decided he would be the father of her children -- damn the powers that be -- and he was. In that way, she was what her generation of told her a woman should be.

But she was also a New Woman, a female writer, a romantic, who wanted to live a life like Byron's. She wanted to live her life with kinetic energy, fight against the forces that would try to hold her back, struggle against the suffering, and win. Of James Bond she once wrote that he could have his mistresses as long as she could have her lovers. Society was hypocritical: it praised adventurous men but damned adventurous women.

...

Reading at Seagram's Museum on May 6, Sullivan expounded on her thesis that Smart had two primary themes in her writing, love and silence. Smart first pursued George Barker with an obsessiveness that was total and blinding, believing as she did that heroic love would save her from her bland, bourgeois, Canadian up-bringing.

But finding her vision far less than realistic, Smart then turned later in life, like many creative women of her generation (Sylivia Plath comes easily to mind), to trying to find a voice for all the women who are silenced by a culture that dominates and subjugates them.

Smart came from a wealthy family, but she spent the prime of her life as a single mother struggling to make ends meet, dying all the time only to write. She knew only too well what she came to call "woman's lot." Smart's second book, The Assumptions of Rogues and Rascals, illuminates her second theme. She "rebelled" (said Scott)? Good God, I hope so.

At one point in By Heart, Sullivan poses the rhetorical question, How then do you survive life's script? "By a rage of will," she says and quotes Smart:

Like this: pray; bang your head; be beautiful; wait; love; rage; rail; look, and possibly, if lucky, see; love again; try to stop loving; go on loving; bustle about; rush to and fro. Whatever you say will be far less than the truth.

"Refuse dismay and battle on regardless," says Sullivan, "which is what Elizabeth did. Indeed, Elizabeth believed the only response to life was 'ecstatic surrender' since life has a will stronger than yours. 'It is not for you to know.' She would always ask herself, 'Can't I possibly be a little braver?'"

Elizabeth Smart, says Sullivan, "lived on a vertical plane, where ecstasy or pain could deliver themselves like shafts shattering the moment." And -- oh! -- she is so sad! Her language has such strength and yet she was so subsumed by her need to love and be loved. She couldn't believe she was a good writer until a man told her she was. But not just any man, a poet. Barker, thankfully, gave her that praise, and Smart gave us her prose.

So full of contradictions, it is difficult to know what to make of Smart's life in our contemporary context. Her absolute devotion to her children might be seen as an attack on women's progress in the workplace, and yet Smart broke through many -- if not all -- of the social taboos of her day (and these days, too). That she is a great writer is gospel. Her life will only grow in significance. Rosemary Sullivan has done her well.

Saturday, January 28, 2012

Milan Kundera

This is the first book review I ever published, over 20 years ago, and its conclusion still rings true today.

Interesting to read this so much later. I can't remember much about the book now. Forgot all about Imagology. But I did remember the 60-year-old waving to the swimming instructor.

The point being, WC Williams and the imagists were right. The concrete wins out over the abstract every time.

On the same page, above the fold, was Derek Weiler's review of Atwood's Wilderness Tips.

*

[Review first published in Imprint, University of Waterloo, Sept 27, 1991]

Immortality

by Milan Kundera

Grove Weidenfeld

Back after a seven year hiatus, Milan Kundera has published a new novel. Probably best known in North America for the film version of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Kundera has returned with a delicate and delightful novel, a novel very much of its time.

Not that its time, the present, is delicate and delightful. Quite the opposite. The present is paradoxical, as is this beautifully heavy novel with a light touch, Immortality.

Translated from the native Czech, Immortality is Kundera's first novel since the end of the Cold War and the restructuring of Eastern Europe. For an expatriate living in France whose last novel studied the intricacies of modern life on both sides of the Iron Curtain before, after, and during 1968's Prague Spring, these must be significant events. And they are. But Immortality sets them in a broader context.

This is not a novel about the end of communism, though the effects of the recent changes are in evidence. This is a novel about Europe(ans), past and present, a contient too told and too much ravaged by supposedly Great Leaders this century to trust too quickly in another promise of renewal.