Of course, later she would win the Nobel and top the NY Times list of "most prominent" novelists, 1980-2005.

I saw her read at Trinity St. Paul's United Church in (I think) 1997 (what fantastic hair!) and walking out afterwards overheard two women:

"You know from a feminist point of view she's interesting."

"Why's that?"

"She doesn't just present women as victims."

*

[This review first appeared in Imprint, University of Waterloo, June 26, 1992]

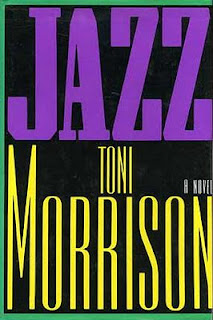

Jazz

by Toni Morrison

Knopf, 1992

Sth, I know that woman. She used to live with a flock of birds on Lenox Aveune. Know her husband, too. He fell for an eighteen-year-old girl with one of those deepdown, spooky loves that made him so sad and happy he shot her just to keep the feeling going.

There is a school of literary criticism that holds to the belief that black women writers are doubly discriminated against in their quest for intellectual recognition. They are, it is said, excluded from the discussions that determine academic excellence first because women's experiences are generally devalued in our culture, and second because white people simply don't try hard enough to understand black people.

Toni Morrison is one of the few writers, along with Alice Walker, to have broken through this cultural barrier. She won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for her novel Beloved and has just released Jazz to somewhat confused critical acclaim. Affirming the notion that institutions of power are unable to understand marginal voices, Time magazine's review of Jazz praised Morrison's literary ability while confessing not to understand her purpose.

The novel's plot is contained in its first sentences, quoted above. Simply put, the novel is about a couple who grow apart as they grow old. He takes a young lover, who leaves him. He kills his lover. Life goes on, somewhat like before. But also radically different. The novel concentrates on its characters, not its plot. It tells us in deeply drawn strokes each individual's quirks and fantasies, and after a while it is difficult to discern the victims from the offenders. Everyone is hurting, everyone is looking for redemption.

Likely this is not what you'd expect from a novel about a love triangle and a murder. But Morrison's point is that there are not easy answers, the roots of the problem run deep. The symptoms may be obvious, but the causes are certainly not. Jazz explores (as a Charlie Parker solo explores; it wanders, but always to the right place) the depth of this theme, celebrating human connections at the same time as it points out the consequences of their failings.

Love's connections may be frail, Morrison is saying, and they are often the cause of much pain and anguish, but they are also life's strongest bonds. Jazz plays with this paradox. The purpose of the novel, then, is simple. Jazz is jazz. That is all. Nothing more, nothing less. And as Louis Armstrong once said, "If you have to ask what's jazz, you'll never know."

As a cultural phenomena, the novel deserves to be discussed within the context of contemporary race and gender relations. A novel about black people in Harlem in the 1920s, Jazz speaks the voices of the marginalized people who feel they've moved up in the world. The readers, however, who know how hollow these dreams of 70 years ago are, can see the tragedy in the characters' ambitions. Just as they can see how little has changed with regards to violence against women.

But Jazz is not an overtly political novel, though in a completely subversive way the novel points out the commonalities that bind all people. These are the connections of emotion, the need to be loved, understood and wanted. And though these connections function on the level of individuals, they are also symptomatic of our culture as a whole.

Says one character: "All kinds of white people are there. Two kinds. The ones that feel sorry for you and the ones that don't. And both amount to the same thing. Nowhere in between is respect."

No comments:

Post a Comment