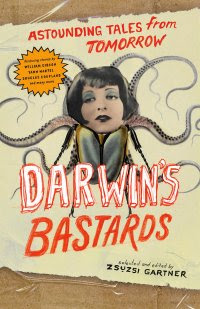

The kids thought the cover was fantastic. "What is that?!"

The book was the centre of a throng, and witnessing the chatter of the SKs on this subject was a pleasure to behold.

Mutants clearly invigorate the six-year-old mind. Equally, many of the 23 stories collected in this anthology invigorated mine.

Divided into four sections (survivors, lovers, outliers, warriors), this book throws down the gauntlet of what a short fiction anthology in Canada can be.

For one, while all of the authors are Canadian, this isn't a book any high school student could claim in boring. For two, Gartner has achieved that elusive balance, one that has stymied her peers for decades - an anthology that effortlessly blends the literary and the popular, genre fireworks and pointy-headed big ideas.

My personal favorites:

- "There is no time in Waterloo" by Sheila Heti

- "Survivor" by Douglas Coupland

- "Notes from the womb" by Anosh Irani

- "This is not the end my friend" by Adam Lewis Schroeder

- The introduction by Zsuzsi Gartner

"There is no time in Waterloo" by Sheila Heti imagines a world in which everyone consults their mother before taking any action. "Mother," however, is metaphor; it's a hand-held device, really. The device predicts the probability of various outcomes. Waterloo, Ontario, is the site of the action. Also the home of RIM and the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. Princess Avenue, where I spent layabout time in the 1980s and early 1990s, features in a prominent role.

"Survivor" by Douglas Coupland is set in the middle of the Pacific on a tiny island, where the n-th season of the CBS hit reality show "Survivor" is being filmed. Meanwhile, nuclear war ends life elsewhere. The "survivors" are survivors. Outwit, outlast, out play.

"Notes from the womb" by Anosh Irani is narrated by a foetus. The story ends at birth.

"This is not the end my friend" by Adam Lewis Schroeder is set roughly 50 years in the future. The USA has melted down into zombieland. Obsessed with celebrity trivia, it has suffered social collapse. To prevent a similar crisis, the Canadian government has outlawed celebrities and built a barrier between the Great White North and its southern neighbour. The story follows the trip of a musicologist, who is researching "rock stars." Travelling with his neice and nephew, he visits Feist, who is living in a remote location in a trailor.

The introduction by Zsuzsi Gartner is charming, funny and intelligent.

Darwin's Bastards is an anthology for every bookshelf.

Some reviews:

- Globe and Mail (March 26, 2010)

- National Post (March 26, 2010)

- Toro (April 8, 2010)

- Straight.com (April 22, 2010)

- Los Angeles Times (May 23, 2010)

- Montreal Gazette (June 11, 2010)

- The Tyee (June 18, 2010)

- Broken Pencil (Aug 5, 2010)

- Geist (Aug 11, 2010)

- Quill & Quire (April 2010)

- The Movie